Sculpture is the Essence of Things

Claudia Mann’s sculptures rear up like archetypes in space filling it with energy, enriching it and transforming it into an entity. They do not require any auxiliary constructions such as plinths or pedestals as the works themselves are much too archaic and strong. Only when the sculptural idea’s positioning in space defies gravity, such as is the case of ‘rack (arm)’ or ‘model for sculptures inside. Studio cast. C.Mann 18.10.2016’ and ‘Cast’ (all 2016), are the works then supported by fragile constructions. They all refer to the human body, so that their reception is especially fertile when the observer allows him- or herself to become involved on a physical level. Several works, such as the bronzes ‘horizon’ (2016) first become accessible to the observer when viewed at the level of their horizons, i.e. from far away, or up close lying on the floor. Others unfold in their real size in front of the viewer when standing, such as ‘Cast’ (2016), or, as a material conception, evade any visual and physical access such as ‘rack(arm) (2016). This aesthetic based on mobility clearly demonstrates that a change of perspective is for the artist of vital importance for the understanding of sculpture and space. Accordingly she also resorts to other media in her work, e.g. video, photography and language which serve as mirrors reflecting her sculptural works. Her starting point is original and down-to-earth in the literal sense. Or put more exactly, it is human, it is her own body which she uses as a model for the interaction of sculptures in a spatial context. Its original sculptural characteristic, subject to the laws of gravity, is the contact with the ground. This explains the special significance which Claudia Mann attaches to the horizontal line in her text ‘I do believe’, which on closer examination could be termed as ‘the ground under one’s feet’. Her art-historical reference points are classical. ‘Cast’ (2016) with its three seams and its diameter refers to Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous drawing on the study of proportions with the ‘Vitruvian Man’ (from around 1490). In this case, however, the sculptural volume of the work exceeds the measurements of the artist’s own body from which it was developed. One of her most important artistic sources of inspiration is the great Michelangelo Buonarroti. She has dealt in depth with his realization that every block of stone has a sculpture inside which needs to be discovered.

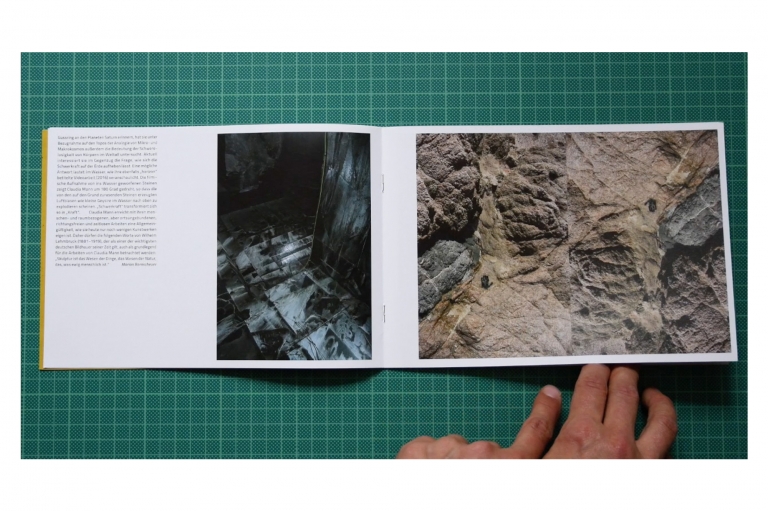

This reference is exemplified by the photographic work ‘Sculptures Inside’ (2014) which shows the inside of a cave in the quarry at Carrara. Claudia Mann has not just photographed the exquisite, coarsely cut material which contains, from a sculptural point of view, an infinite number of potential sculptures by offering a projection surface for an inexhaustible wealth of ideas; but has turned the motif upside-down. By doing this she dismantles familiar spatial order and democratises that above can be just as well below, and outside can just as well be inside.

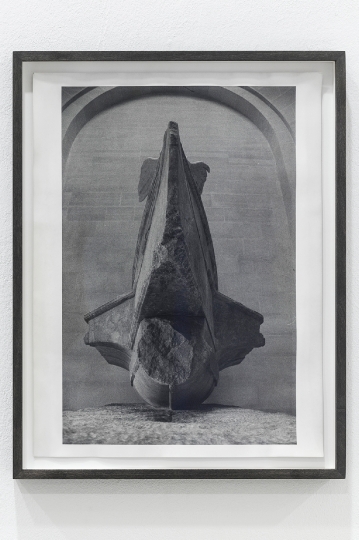

In turn Claudia Mann uses Michelangelo’s idea of sculpture enclosed within the material as an artistic starting point in relation to mankind. As a result an analogy arises to human funerary culture, which the artist used in the group of works ‘First Sculpture is Grave’ with texts, drawings, photographs and sculptures. ‘Cast’ (2015) a threedimensional plaster sculpture arose by filling in a hole in the ground which Claudia Mann had dug to correspond to the depth and width of her own body when sitting. The same technique formed the basis of the work ‘Aero’ (2016) produced of glass fibres. In this case however, the sculpture is larger, as the bodily measurements used were in a standing position with upstretched arms and furthermore it is hollow. ‘Aero’ is appropriately diaphanous and appears light and airy in contrast to the opaque and very heavy ‘Cast’ of 2015. Both sculptures share the basic shape of the triangle which Claudia Mann considers the perfect form because it possesses of all geometric shapes the greatest simplicity and aerodynamic qualities while at the same time having ideal tectonic stability. Another fact that both sculptures have in common is that their surfaces or outer skins are encrusted with the soil from whence they were born thus reflecting not only the natural cycle of birth and death but also the affiliation of nature and sculpture.

Furthermore, ‘Aero’ with its hollow structure opening at the top is a space within a space. Thus further analogies to Egyptian sarcophagi, objects of particular photographic interest for Claudia Mann, become apparent, because they represent in their function as a sculptural cocoon for the corpse also spaces which were developed in the context of a funerary cult. The sculpture ‘rack(arm)’ (2016) may be considered pars pro toto of this group of works. The artist excavated the shape in the soil manually to the depth of one arm’s length and finally casting it in glittering mineral polyester resin. The sculptural moulding of an arm refers art-historically to Bruce Nauman’s work ‘From hand to mouth’ (1967). At the same time it evokes, by its positioning above the head and out of reach, yet another much older work of art which has even greater significance for her: namely

Michelangelo’s fresco of the Creation of Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The way in which Adam reaches towards God’s life-giving finger is very similar to the way Claudia Mann stimulates the observer, with the sculpture of an arm installed out of reach above his head, to receive the sculptural ideas of the artist. If the exterior spaces permit the artist to find her sculptures by digging in the earth then her sculptural search in interior spaces is limited by predetermined aspects. The reference point or ‘horizon’ emanates not only from the floor but now also the ceiling and here she chooses the most interesting places regarding matters of form and casts or moulds using plaster flat roundish shapes. In this way it is possible to generate three-dimensional sculptures from two-dimensional surfaces. This is where Claudia Mann derived her thesis ‘Sculpture is Ground’. The relief thus formed is then placed on the floor directly below the moulded part of the ceiling. In this way a new and ideal space within a space arises between the perfectly matching positive and negative forms. Not only in the case of the ceiling moulding but also casts arising from holes in the ground such as ‘Aero’ and the forms like the hollow, two-part bronze ‘horizon’, it is the sculptures’ ‘skin’ which create new spaceWhen is all said done, the question must be posed whether these works go far beyond the traditional concepts of ‘sculpture’ and should in fact be regarded as ‘spaces’, so that these two terminologies ideally merge into one another until congruence is reached. Be that as it may, they are to be understood as ‘materialised reflections’ on sculpture and space.

In her works Claudia Mann looks into the relationship between the body and space in all dimensions as well as above and below the horizon line and/or the earth’s surface In works such as the two small-format bronzes ‘horizon’ (2015 and 2016), with their cast rings reminiscent of the planet Saturn, she referred to the analogy of microcosm and macrocosm and also studied the significance of weightlessness for bodies in outer space. Conversely she is currently interested in the question as to how the force of gravity on planet Earth could be suspended. A possible answer would be, in water, as can be seen in her video film (2016) also titled ‘horizon’. The video depicts stones being thrown into water but Claudia Mann shows the film turned by 180 degrees, so that the bubbles generated by the stones speeding towards the bottom appear to be like miniature geysers exploding upwards in the water. The ‘gravitational force’ thus transforms into ‘force’. With her human and spatial works which are neither bound by place, direction or time, Claudia Mann’s work has attained a universal validity which only applies to few works of art today. That is why the following words by Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881-1919), who was considered to be one of the most important German sculptors of his day, seem most appropriate and fundamental for Claudia Mann’s work:

‘Sculpture is the essence of things, the essence of nature, that which is perpetually human’.

Marion Bornscheuer

(translation from the German by Robert Payne)